Investment Memo: Nintendo (7974:JP / NTDOY:US)

Medium-term risk/reward looks reasonable for the stock, but the moat around the House of Mario faces threats in the long-term

Disclaimer: This is NOT investment advice. This is just me sharing my thoughts.

Investment Conclusion

At a high level, I see three primary value drivers for Nintendo:

Reduction of revenue cyclicality

Gross margin expansion from increasing digital sales of video game software

Reinforcement of economic moat via investments in IP expansion and mobile gaming

In this note I assess each of these in detail by examining the company’s background, strategy, competitive advantage, and management team. I also discuss how my view translates to a financial forecast, how that forecast compares to consensus, and how Nintendo’s valuation stacks up on a relative basis.

But first, to summarize my thesis up front, I will outline my conclusion on each of these drivers in turn.

Regarding the first driver, reduced revenue cyclicality, I see two possibilities. The first is that Nintendo’s latest console, the Switch, marks a change in strategy toward more of a hardware-software ecosystem. Rather than betting the house by reinventing the hardware for each new console, Nintendo is likely to position future consoles as upgrades to the Switch, i.e. a Switch 2, Switch 3, Switch Pro etc. Similarly, updates to the major game franchises could become more frequent and iterative, as they would no longer be tied to new console releases. This could lead to a world in which consumers regularly upgrade their Switch consoles, just as they do their smartphones, and are able to interact with their favourite game franchises more frequently and consistently. This should end the boom-bust pattern that has characterized much of Nintendo’s history to-date. The second possibility is that the status quo continues more or less and revenue remains cyclical, albeit helped by future games becoming backwards compatible and by some modest subscription revenue from Nintendo Switch Online accounts. Such a scenario could reflect Nintendo’s insuperable desire to innovate in hardware, their belief in the necessity of long and deliberate release cycles for major games, or both. It could also reflect the fact that, even if future consoles are new versions of the Switch, upgrade cycles are unlikely to be short enough across their customer base to reduce revenue cyclicality significantly. I believe the second possibility is more likely.

I have a positive view on the second driver, gross margin expansion. Generally speaking, the world has moved away and is moving further away from physically packaged media and software. Nintendo has been slower in this regard, but is catching up. Digital sales of video game software have expanded as a share of software revenue from 25% in FY 2019 to 51% in 1H FY2023. I expect this to continue and believe this will increase margins over the coming years.

The third driver, investments in IP expansion and mobile gaming, is not entirely distinct from the first, as increased prominence of Nintendo’s IP and a robust mobile gaming business would both support the company’s core business and likely make revenue less cyclical. I believe Nintendo’s economic moat, its IP, is under threat from new gaming and media consumption habits taking hold in society, especially among today’s younger generations. If Nintendo fails to adapt to these, then the value of their IP, which is perhaps second only to Disney’s today, might become eroded over time. A number of IP expansion initiatives that are bold by historical standards are underway, including theme parks and a Super Mario movie, but their implementation via partnership will lead to negligible direct upside for Nintendo and also might fail to create the synergies with the core business that management instead hopes for. Similarly, management is singing the right tunes about taking mobile gaming more seriously, but to-date this has not manifested in any tangible way. Overall, Nintendo’s approach to investment in both IP and mobile seems overly cautious and this has led to underinvestment in my view, especially in light of the fact that the company regularly holds 75-80% of its Balance Sheet in cash and investment securities.

To my mind, there are effectively two conclusions on Nintendo, depending on the time horizon. On a short to medium term view, the risk/reward strikes me as pretty reasonable. On the one hand, there is potential upside from gross margin expansion and also from the fact that the next console (whether that be a new Switch or otherwise) might not be fully factored into consensus estimates. On the other hand, the downside seems somewhat limited by an undemanding valuation and by the company’s strong financial position. On a long-term view, however, I do not see revenue cyclicality reducing significantly and I do see a risk that Nintendo’s valuable IP might become less valuable over time, thereby narrowing the economic moat around the business. These trends could eventually put pressure on the stock.

Company Overview

Nintendo was founded in 1889 as a manufacturer of playing cards and went public in 1962 on the Japanese stock exchange. Nintendo’s third President Hiroshi Yamauchi eventually pivoted the business at first into the toy industry and eventually into the video game sector. He was helped in these efforts by the innovations of Gunpei Yokoi, a recent graduate in electronics whose talents Yamauchi recognized and unleashed. Today, Nintendo is renowned as one of the world’s premier video game console manufacturers and game publishers. Over the years it has released acclaimed consoles, such as the Game Boy, Wii, and Nintendo DS. Its latest console, the Nintendo Switch, has seen considerable success. Some consoles, however, have been duds, like the Wii U and Game Cube. Nintendo has also created some of the most loved video games and game characters in history, such as Super Mario, Donkey Kong and Zelda. It also has released Pokemon games and owns a minority (~33%) stake in the Pokemon Company. Nintendo claims three of the top 10 best reviewed games of all time on Metacritic.

Nintendo makes nearly all its money from the sale of console hardware and game software. Currently the Switch represents 98% of this. The margins on hardware and software are very different, as hardware tends to be sold at a minimal margin or at breakeven. In FY 2022 (year ending March 2022), hardware represented 48% of video game platform revenue (down from 53% in FY 2021) and company-wide gross margin was 56%. Software revenue consists of revenue from games packaged and sold physically, downloadable versions of the former, download-only content, and Nintendo Switch Online subscription fees. Software that is sold physically is lower margin and so the company has begun to draw focus to its Digital Sales (i.e. software revenue excluding physical sales), which has increased as a percentage of software revenue from 25% in FY 2019 to 51% in 1H FY2023. The majority of software revenue (79% in FY 2022) comes from games that Nintendo develops and publishes itself. This partly reflects revenue recognition, as Nintendo recognizes third-party software revenue based only on its sales commission as opposed to the full game price. Looking at total game value currently sold for Nintendo Switch, over half is now coming from third-party publishers.

The majority of Nintendo revenue is from one-time purchases and therefore tracks the life cycles of game consoles. This is true of both hardware and software, as new games tend to be tied to hardware releases. Nintendo generates some recurring revenue from Nintendo Switch Online subscriptions, which have been growing but which I estimate represent less than 10% of video game revenue currently. Nintendo generates ~80% of video game platform revenue outside of Japan (43% from the Americas in FY 2022, of which most is the US, and 26% from Europe). This makes consolidated revenue, which is reported in Japanese Yen, sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations. Nintendo also makes a small amount of revenue (3% of total) from mobile games and IP-related initiatives.

Strategy & Competitive Advantage

Core Hardware-Software Business

Nintendo’s core business is cyclical owing to the primacy they place upon designing and selling video game hardware. Each console has a life cycle during which sales volume builds to peak and then declines to an eventual installed base, the size of which measures the success of the console. While consoles vary in degrees of success, technological advances place a shelf-life on all consoles, as is true for hardware in general. The chart below illustrates this cyclicality by plotting the sales volume of Nintendo consoles going back to 1998. Console lifetimes range from 5 to 12 years, with the time from launch to peak sales ranging from 1 to 5 years and the time from peak to trough ranging from 4 to 8 years.

Console software sales volumes follow similar cycles (see chart below) but tend to peak 1-3 years after hardware volume peaks.

Nintendo views their core business as an integrated hardware-software business and ties game software to console launches. New games in their most popular franchises are released when Nintendo believes new hardware unlocks new functionality, allowing them to reinvent some aspect of the gaming experience. Major updates in the Zelda franchise have sometimes been 4-5 years apart, for example, with Breath of the Wild having come out in 2017 and a sequel slated for next year. At a high level, their approach of tying games to hardware releases has made their deployment of gaming IP cyclical as well. Owing to the infrequency of major game updates, the IP is arguably under-monetized.

The economics of the core business reflect this cyclicality. During upswings of the console cycle, Nintendo can generate excellent cash returns on invested capital, but these can rapidly compress as the cycle matures. This effect is exacerbated by the fact that not all their consoles are a success. In FY 2016, when 3DS console sales were decent but declining and the Wii U was failing to take off, I calculate Nintendo generated a free cash flow margin of 10% and, stripping out excess cash and investment securities, underlying cash returns on invested capital (CROIC) of 27%. In FY 2017, as sales of these former consoles dried up but before the Switch had taken off, Nintendo generated only a 2% FCF margin and 3% underlying CROIC. In FY 2018 and FY 2019, as the Switch caught fire, FCF margin shot up to 13-14% and CROIC to 48-50%.

Often, the brand of a company can be damaged by the release of a bad product and so, by contagion, can the prospects of their future products. Yet Nintendo has been able to fail in one console generation, as with the Game Cube, and then come back and win the next generation, as with the Wii and DS. From a hardware perspective, the Wii and DS were more innovative than their predecessor, but to me this pattern hints at where the company’s true economic moat might lie – in their gaming IP. Gamers return to Nintendo after a poor console release not because they are wowed by the hardware, but because they want to interact with Mario and Zelda etc. The strength of this IP has allowed Nintendo to recover from poor hardware multiple times in the company’s history, but because the IP’s deployment is tied to hardware releases, it has not been able to insulate the business from cyclicality.

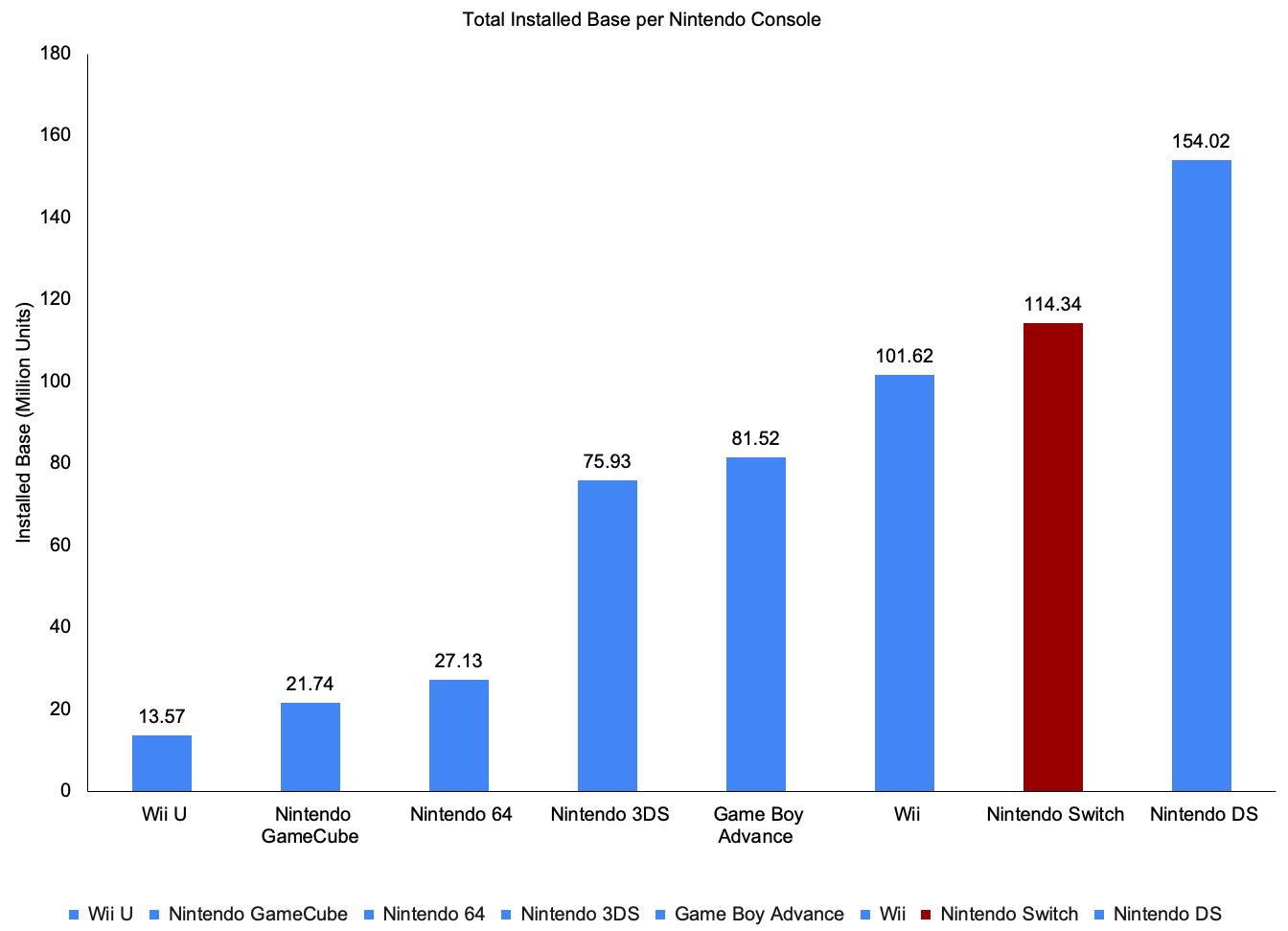

Nintendo’s current console, the Switch, has built an installed base to-date of 114 million units, behind only the Game Boy and DS internally and fifth currently on the ranking of all console installed bases. Even assuming future volume declines, it is on track to become the best-selling console ever, surpassing the PlayStation2’s 159 million units. A good deal of its success lies in its innovative combination of handheld and at-home functionality, effectively layering previously distinct markets on top of one another. Nintendo also launched a number of first-party blockbuster games alongside the hardware launch that provided customers with an immediate reason to ow the console. These include The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (rated by some as the best video game ever) and Super Mario Odyssey. Other games since then have also done excellently, such as Animal Crossings: New Horizons, which was released in March 2020 and has since sold 40 million units (the second best performance of all first-party Switch titles). You’ll notice the release was fortuitously timed alongside people’s initial retreat into lockdown at the outset of Covid.

But despite the success of the Switch, the long-term outlook for the core business is uncertain. Some believe the Switch to be another console with a finite lifecycle. They expect sales volumes to decline over the coming years and speculate over what next generation console might replace it and when. Others believe the Switch marks the start of a fundamental business model transition toward more of a platform strategy, in which future hardware releases become iterative updates to the Switch and the company tries to retain the current user base versus reacquiring it with a brand-new console. There is some evidence to support this second view, such as Nintendo Switch Online (users pay an annual fee for access to a modest game library, online multiplayer, voice chat, cloud storage), Nintendo Accounts (a centralized cloud link to all your Nintendo devices, emulating iCloud etc), the fact the majority of Switch platform game value now comes from third-party game developers (unusual compared to past consoles), recent management hints that games for the next console will be backwards compatible, and the increased amount of downloadable add-on content now available.

The implication is that the former scenario would see continued revenue cyclicality, while the latter has the potential to decrease this cyclicality, as each new console becomes more a question of retaining users within an ecosystem than one of gambling on the latest hardware innovation. One thing to add though is that reduced cyclicality in this scenario, at least from a hardware perspective, also depends on a sufficiently frequent upgrade cycle. To me it is debatable whether or not gamers would upgrade their Nintendo Switch every two years. The upgrade cycle for smartphones has been lengthening as a result of product innovation becoming more incremental, implying any upgrade to the Switch would either need to be more powerful or need to be differentiated in some way. The former has not historically been Nintendo’s strength or value proposition. The latter entails the risk that attempted differentiation lands poorly.

The uncertainty regarding potential changes to the business model is important, because Nintendo faces risks from structural cultural and technological shifts taking place in the gaming sector and in wider society. These shifts are best described by what tech analyst Ben Thompson refers to as the dichotomy between scarcity and abundance. Economic value historically has stemmed from scarcity, but the internet has shifted value toward abundance. Thompson compares now defunct video app Quibi to TikTok. Quibi tried to shoehorn the traditional Hollywood movie-making process into a mobile app optimized for viewing on the go by serving you a curated library of quality short videos. It did not take. TikTok, on the other hand, embraces the sheer volume of mobile content and uses this alongside your own preferences as a reinforcement mechanism to serve you videos algorithmically. This likely oversimplifies, but Quibi sought value in scarcity, while TikTok found it in abundance.

The world of abundance seems to have spread to media and gaming. In such a world, the cognitive load of finding and choosing content is greater, which pushes consumers toward not wanting to do it at all. They either want to have it done for them (algorithmically like TikTok) or they want to be able to stick to well-known and loved IP. For this reason, as Matthew Ball has pointed out, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has been able to increase its gross revenue per film even as the production quantity has grown from 1.2 films per year to 3-4 and even as the number of competing franchises has tripled. People would seemingly rather spend more time inside a fantasy world they love than find a new one. This desire extends to consuming the same content via different mediums. After the release of the Witcher 3 video game, the 25-year-old Witcher book series hit the NYT best seller list for the first time. When The Witcher hit Netflix, the video game saw its player count grow 3-4x and the book series returned again to the best seller list. Similarly, in a world of abundance value comes from engagement, social interaction, and a network that proliferates through the noise. The games played by young people today embrace this dynamic and follow a more iterative, gaming-as-a-service development cycle, tailoring updates to how users play the games to create a feedback loop. In September 2022, Fortnite had >250M active users and Roblox had >200M, according to activeplayer.io. By contrast the Switch has an annual active user base of 106M, so presumably the monthly active number would be non-trivially lower.

The age distribution of that annual active user base is also instructive. The most active users range fall roughly within ages 20 to 35. There are more annual active users aged 42 than 18. Below age 20, the active user base drops off quite rapidly. Compare this to Roblox players, reportedly 67% of whom are under the age of 16, and to Fortnite players, reportedly 63% of whom are between the ages of 18 and 24. It is telling that the Switch appeals to a significant number of older gamers that would have grown up playing on Nintendo consoles. There is an element of nostalgia driving their continued engagement with Nintendo IP. Such nostalgia continuing as a driver of engagement relies on younger generations feeling for Nintendo in the future what older generations feel today. But if they have grown up playing different games on different platforms, there is an argument they might not. Perhaps today’s young players will mature and become more active Switch users over time, but such a view should be tempered by the fact that, as mentioned, these new games might reflect a paradigm shift toward abundance rather than great games in isolation.

It strikes me that Nintendo continues to view the value of its IP as stemming from scarcity. This is why they update their major game franchises infrequently and view the quality of those games as inherently related to a long and considered release cycle. To be sure, this has produced and continues to produce some fantastic games, but it risks becoming out of sync with new, emerging gaming habits. Nintendo needs to ensure their IP stays current and relevant even as the world around it changes, otherwise they risk putting a shelf-life on its value that is tied to the generations most familiar today with Mario and Zelda. This could erode their economic moat over time, although I should caveat this by pointing out that such a risk would necessarily take years to manifest and so is a long-dated one.

Nevertheless, how might Nintendo mitigate this risk? Any attempt to modernize by updating their development cycle in a major way would probably require the company to overhaul its culture more or less entirely, which seems unlikely in the short or even medium term. But the company can still support their core business by investing in the reach and relevance of their IP.

Theme Parks and Non-Game Media

Nintendo is indeed investing in expanding its IP and has publicly outlined to investors how this now forms a key part of company strategy. A number of initiatives are underway. Super Nintendo World opened at the Universal Studios Japan theme park in March 2021. A second Super Nintendo World will open at Universal Studios Hollywood in early 2023. There are plans to open further locations in Orlando and Singapore over the coming years, as well as a Donkey Kong area in Universal Studios Japan in 2024. A new Super Mario Bros movie is scheduled for release in April 2023, produced by Universal’s Illumination Studios. They have opened physical stores in New York and Tokyo, with Osaka to follow. Nintendo also completed its acquisition of Dynamo Pictures this October, with plans to rebrand it Nintendo Pictures for further non-game media projects. All of these initiatives are bold by historical standards.

Yet there are signs that management is not taking the importance of these initiatives seriously enough. By partnering with NBCUniversal on theme parks, Nintendo has outsourced the day-to-day operations and the majority of revenue. Similarly, while Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto has had significant creative input into the new film, Universal is responsible for production and will keep most of the revenue. As a consequence, these initiatives will have little direct financial impact. For example, one source estimates Nintendo’s licensing deal with NBC Universal gives them a 9% cut of revenue. NBCUniversal made $6.2B in 2019 across its four theme parks. Assuming Japan represents 25% of that and that Super Nintendo World (generously) represents 50% of Japan, a 9% cut would generate ~¥10B for Nintendo at today’s exchange rate, or less than 1% of total revenue. By contrast, in 2019 Disney saw their owned and operated theme parks represent 38% of total revenue.

In April 2017, Tatsumi Kimishima, Nintendo President at the time, said that theme parks and movie deals were less for potential profits and more for synergy with the core business. While the initiatives above will certainly aid the prominence of their IP, it strikes me that Nintendo is potentially underestimating the level of investment that is required to drive such synergies.

Having opened the original Disneyland in 1955, Walt Disney had the following to say about the experience of opening and operating a theme park:

The one thing I learned from Disneyland [is] to control the environment. Without that we get blamed for things that someone else does. I feel a responsibility to the public that we must control this so-called world and take blame for what goes on.

Disneyland is not just an experience that Disney controls themselves, but an end-to-end immersion in only Disney’s IP.

Now contrast this to the current and future Super Nintendo Worlds, where not only is the experience controlled by a third-party, but also the IP is competing with other brands and experiences for space and attention. The brand affinity that an end-to-end exclusive experience engenders and commands is surely much stronger than that where a family might one moment have a go on the Mario Kart ride and the next moment pop into Hogwarts. There is a risk, in short, that the current implementation of Nintendo IP at theme parks might fail to build the emotional bonds with park visitors that will truly support the core business.

The best pushback against this is to point out that purchasing land to build and open an exclusive Nintendo theme park would be very expensive (according to the Park Database, it costs between $2 billion to $4 billion to build and open a mega theme park) and fraught with execution risk for a company that has no experience in taking on such a project. Both of these considerations put the economics of an owned and operated theme park in doubt. One would have to make several leap-of-faith assumptions to envisage everything working out.

And yet, the high end of $4 billion represents 29% of Nintendo’s total FY 2022 ending cash and investment securities. Given the amount of capital Nintendo has available to deploy and the potential long-term support that a fully-fledged mega theme park might offer the company’s brand and IP, perhaps it would not have been crazy to try.

In any case, the debate seems moot at this point, as Nintendo remains deeply focused on their core hardware-software business. They seem driven by judiciousness about IP expansion for fear that ubiquity of their characters might damage their brand. While I think this conservatism could prove costly over the long-term, one can partially forgive the company for it after the 1993 Super Mario Bros movie disaster.

Mobile

Global mobile gaming revenues are estimated to reach $104 billion in 2022, over half the $203 billion global gaming market, and are growing faster than other segments. Yet Nintendo has never taken mobile seriously, a long-standing source of criticism of the company. 2016’s Super Mario Run is the 14th most downloaded mobile game ever but achieved only ~$75M in revenue thanks to a poorly conceived monetization strategy. Contrast this with Tencent’s Honor of Kings which has grossed ~$1.7B. The downloads achieved by Super Mario Run is evidence of gamers’ continued interest in Nintendo IP, while the meagre revenue is evidence of the company’s lack of interest in mobile.

Nintendo maintains a stubborn belief in the unique attachment of the value of their IP to the hardware that delivers it. But their arguments to justify such a belief are tenuous. At the company’s Corporate Management Policy briefing in FY 2021, Nintendo’s President Shuntaro Furukawa said the following:

One thing we always pursue with our integrated hardware-software entertainment is that even the touch and feel of the product should be fun. For us, it began in 1889 with the feel of Japanese playing cards (hanafuda), and we have remained mindful of the importance of this sense of tactile interaction through every generation of controllers that connects players to our games. You can find this reflected in the Nintendo Entertainment System, which has two controllers with plus-shaped directional pads.

But I could link almost anything physical to anything else physical via the notion of “tactile interaction”, for example the fruit I pick out at the supermarket via examining its ripeness in a “tactile” way to the steering wheel in my car that I manipulate in a “tactile” way to navigate corners. The reality is that the current hardware-software business has very little to do with the original playing card business, except via connection to the broad entertainment sector. Nintendo’s then-President Hiroshi Yamauchi was able to pivot the business aggressively into the gaming and then video-gaming space precisely because he did not anchor on what playing cards did or did not represent.

Implicit to Furukawa’s comments is a defense of the company’s seeming lack of interest in mobile gaming to-date. This does appear to be changing somewhat and Nintendo now frames mobile within the company’s broad strategy to invest in IP to maintain its relevance (see slide pasted above in the previous section). Yet, given they still only operate five mobile games and given the recently launched Pikmin Bloom, developed by minority-owned Pokemon Go creator Niantic, has reportedly generated only $5M in revenue, I get the impression again that Nintendo underestimates the level of investment that is required.

Nintendo’s Economic Moat

Considering all the above, the key questions are to what extent does Nintendo possess an economic moat and to what extent is it likely to be durable. To my mind, their world class gaming IP does form an economic moat around the business. It is the power of this IP that has allowed them in the past to reacquire users to a new console system after having disappointed them with the previous system. It is this IP that has allowed them to generate excellent cash returns on invested capital during the upswings of console cycles. But they have also underinvested in their IP and under-monetized it. It has not helped insulate the business from cyclicality. As such, it strikes me as a suboptimal moat.

The company is now at a fork in the road. If they truly are pivoting their core business to a more platform-oriented, iterative model and if they truly embrace the importance of investing in their IP across offline initiatives and mobile, then their economic moat has the potential to strengthen and widen. But if management fails to recognize the emergent trends in gaming and continues with more or less the same strategy, albeit with some higher margin revenue from increased digital sales and online subscriptions, with a bit less cyclicality thanks to backwards compatibility, and with investments in IP via partnerships, then they risk the erosion of their moat over time as the deployment of their IP falls increasingly out of line with how people consume media and interact with games.

Management

Nintendo management under President Shuntaro Furukawa hits all the right notes when outlining strategy, but retains a conservatism and seeming belief in the inseparability of their IP from hardware. Hiroshi Yamauchi, the father of modern Nintendo, believed that people “…do not play with the game machine itself. They play with the software, and they are forced to purchase a game machine in order to use the software.” His successor, Satoru Iwata, when asked in 2012 about a potential move into mobile gaming, said “If we did this, Nintendo would cease to be Nintendo.” This kind of thinking is in stark contrast to the risks taken by Yamauchi, who showed no such moral attachment to playing cards. The comparison may be a little unfair in that Yamauchi was desperate to diversify revenue and had already made several failed attempts, while Iwata was speaking from a position of strength. Strength can breed intransigence, but flexible thinking will prove crucial to the company’s future, as the coming years and decades are likely to entail paradigm shifts in gaming and media.

Executive Officers at Nintendo, including the President, are paid a mix of fixed, performance-based, and stock-based compensation. Stock-based compensation appears to be much less liberally used than in the US. In FY 2022 the President and the other top two company executives, including creative director Shigeru Miyamoto, were paid a mixture of fixed and performance-based compensation, where in each case performance-based compensation represented more than 70% of the total. Performance-based compensation is linked to the trailing three-year average consolidated operating profit and allocated based on the seniority of the executive. Overall, it seems that such a structure creates decent alignment with long-term, fundamental investors.

Financial Forecast

You can find my financial model linked here. This section runs through my forecast and the key assumptions made, which might be most helpful in conjunction with reviewing the model itself. Also feel free to make a copy and play around with some of the assumptions.

It is worth reiterating that Nintendo’s financial results are sensitive to exchange rate fluctuation. When the yen depreciates, which it has significantly so far this year, consolidated revenue benefits. Gross margin also benefits from yen depreciation, because, while ~80% of sales are made abroad, ~70% of PP&E is in Japan, weighting production costs toward local currency, although some of this is offset when Nintendo needs to purchase materials in foreign currency. SG&A expenses also grow when the yen depreciates as the advertising expenses of foreign subsidiaries translate back into higher yen amounts on the consolidated P&L. This offsets some of the benefit to EBITDA of yen depreciation. In my forecast, I reflect the currency by using the current USD/JPY and EUR/JPY exchange rates and calculating implied average rates. I do not attempt to forecast where I think currency rates might move.

Management is guiding for 19 million Nintendo Switch hardware units in FY 2023, down 18% year-over-year. This guidance was downgraded from 21 million units at the most recent 1H FY 2023 results. Originally management had attributed lower volumes year-over-year purely to production constraints owing to the chip shortage, but they now appear to acknowledge that lower demand is also playing a role. I use 19 million units for my FY2023 forecast, but do not credit volume with recovery in FY 2024 and onwards. I accept the reality of supply chain issues but I also think Covid created a significant demand pull forward (inventory turnover was 9.1x in FY 2021 vs an average 5.8x over FY 2018 – FY 2020) and so believe we are past peak sales volumes for existing Switch models. Assuming sales volume that falls from 19 million units in FY 2023 to 4.5 million units by FY 2027, my forecast implies the current Switch console reaches an installed base of 166 million units, still making it the most successful console ever. The rate of volume decline my forecast assumes is in keeping with past consoles, nearly all of which saw volumes fall rapidly once past peak.

I derive hardware revenue using an ARPU estimate weighted by model type and adjusted for currency movements. I forecast software volume using an attach rate estimate (cumulative software volume / cumulative hardware volume), which implies that attach rate rises from 7.6x for the Switch in FY 2022 to 9.5x by FY 2027. This is slightly less than the Game Cube, which achieved Nintendo’s highest ever attach rate of 9.6x but on low volumes. I derive software revenue via an estimated ARPU using the same approach as for hardware. I also make estimates regarding Nintendo Switch Online in order to forecast subscription revenue discreetly and my forecast implies recurring revenue increases as percentage of total video game platform revenue from 7% in FY 2023 to 18% in FY 2027.

In my revenue forecast I also make assumptions about a future console. While we have no information on what might be coming, it would be overly punitive to model declining Switch revenues and make no assumptions for a next-gen console. According to various news reports, this could be a either a new Switch model, e.g. a Switch 2 / Switch Pro, or an entirely new console. My forecast is deliberately agnostic about this. But based on these reports, I assume the console drops mid calendar year 2024, i.e. in FY 2025, at a price point of $399 (above the current OLED model at $350). I model hardware volume as 60% of the volume the Switch achieved in its first three years and model software using an attach rate comparable to that of the Switch in its first three years. I assume software is priced similarly to current Switch software.

For simplicity, I model Mobile and IP Related Income using a growth rate. While I could estimate the impact of the various IP initiatives, these are unlikely to have a big impact as explained above and so I simply forecast 10% annual revenue growth for this line to give the company some credit for focusing more on expanding IP.

All in all, I get to a consolidated revenue estimate of ¥1,638B for FY 2023, slightly below guidance of ¥1,650B. The company recently upgraded guidance from ¥1,600B, despite having lowered hardware volume guidance, as a result of updating their average exchange rate assumptions, which were previously 115 and 125 for USD/JPY and EUR/JPY respectively, well below what spot rates imply. I project revenue to decline 12% year-over-year in FY 2024 and 9% year-over-year in FY 2025, before rising 28% in FY 2026 and 1% in FY 2027 as sales volumes from the next console kick in.

There are lots of moving parts within gross margin. On the positive side are the yen depreciation and, importantly, a higher proportion of digital revenue, but on the negative side are a higher share of OLED Switch volumes (which is lower margin), higher raw material costs owing to the chip shortage, and higher transportation costs. In 1H FY 2023 the positives and negatives offset each other and gross margin was essentially flat year-over-year. I assume that dynamic holds for the full year and so keep gross margin flat at 56%. Thereafter, I assume that the proportion of digital revenue continues to rise and has a positive impact on gross margin, increasing it to 57.5% in FY 2024 and 59% in FY 2025. But I then forecast that gross margin drops back down to 55% in FY 2026 and FY 2027, reflecting the launch of a new console and consequent increase of lower margin hardware revenue.

Within SG&A, I assume advertising as a percentage of revenue increases from 6% in FY 2022 to 9% in FY 2023, to reflect the yen depreciation, before decreasing to 7% the following year. I model a spike to 9% again in FY 2025 to coincide with the launch of the new console. I end up with an EBITDA margin of 32% in FY 2023, down from 36% in FY 2022. My EBITDA margin forecast then averages 35% over FY 2024 through FY 2027.

I estimate Nintendo will convert 66% of EBITDA into Free Cash Flow on average over the next 5 years, resulting in an average FCF margin of 23%. Net working capital contributes positively to my FCF estimates, as I assume that inventory levels normalize gradually over the next three years as the effect of the chip shortage subsides. Also included in my FCF estimates is ¥150B of capitalized software related to game and non-game software, per the cash utilization plan the company disclosed in its FY 2023 policy briefing presentation.

I measure CROIC on both an underlying and all-in basis. Underlying means I attempt to strip out excess cash, deposits and securities from invested capital, while all-in means I include cash, deposits, and securities in invested capital. In attempting to strip out excess cash, I assume that steady state cash is 4% of revenue. In FY 2021, during the peak of Covid when the Switch was in huge demand, I estimate underlying CROIC reached nearly 190%, driven by an expansion of FCF margin to 35% from 26% the previous year and of invested capital turnover to 5.4x from 3.6x the previous year. CROIC then subsided to 77% in FY 2022 and on my estimates will be 73% in FY 2023 and will average 73% over FY 2024 - FY 2027, albeit with some lumpiness.

On an all-in basis, I calculate CROIC to have reached 35% in FY 2021 from 23% the previous year. I estimate all-in CROIC of 16% in FY 2023 and averaging 14% over FY 2024 - FY 2027. The significant difference between all-in and underlying CROIC reflects the amount of cash, deposits, and securities that Nintendo holds on their Balance Sheet, representing 64% of total assets in FY 2022 and 68% of total assets on average over the next five years on my estimates. If I were also to include investment securities recorded within long-term assets, then the figure would average 79% over the next five years. Nintendo holds no debt.

Japanese companies are known for holding lots of cash, but in Nintendo’s case they justify this via the nature of the console cycle, which requires them to hold cash a) for investment in future hardware and software and b) to protect the business from potentially unsuccessful console releases. This seems reasonable but is arguably too conservative. The company has room to be more aggressive in its IP investments, in my view. The total cash utilization plan mentioned above earmarks up to ¥450B for investments over the “mid to long term” in game and non-game software and in “expanding consumer relationships”, but this figure represents only 22% of total FY 2022 cash, deposits, and investments. Other potential uses of future cash include buybacks and acquisitions. They completed a ¥95B buyback in FY 2022 and have bought back a further ¥51B so far in FY 2023. They also acquired Dynamo Pictures this year for only ¥35M. I do not assume further buybacks and acquisitions in my model beyond what has been announced. I assume the company continues to pay out 50% of net profit as dividends.

Forecast versus Consensus

The table at the bottom of this section compares my forecast against consensus numbers, as sourced from Tikr.com. You can see that over the next three years, across all key line items, I am quite far below consensus. The one exception is perhaps Free Cash Flow, where I am only 2-4% below consensus numbers in FY 2024 and FY 2025. I suspect this reflects my expectations that a normalization of inventory levels, as the chip shortage eases and Nintendo is able to assemble and sell down the current overhang of unassembled inventory, will benefit FCF over the next few years.

In general, it would seem that consensus it less negative about the trajectory for declining Switch volumes over the next few years. Yet I do not think my forecasts are too pessimistic in light of the lifecycles exhibited by past consoles and in light of the demand pull-forward created by Covid. Just compare the chart in the Financial Forecast section above showing my projected volumes for current Switch models to the first chart in the Strategy & Competitive Advantage section that illustrates past console cycles. To reiterate, my hardware volume forecast still implies that by FY 2027 the current Switch console will be the best-selling console ever. Similarly, my software volume forecast implies that the Switch achieves the second best attach rate of all Nintendo consoles, despite record hardware volumes. Neither of these landing assumptions strike me as overly bearish.

Looking at FY 2026 and FY 2027, however, my forecasts are significantly higher than consensus numbers. This reflects the ramp up of hardware and software volumes from the new console (i.e. a Switch 2/Pro or something else).

All in all, this paints an interesting picture, as it implies consensus is forecasting modest downside to existing Switch console volumes and revenue, but no upside from future console volumes and revenue. In light both of past performance and potential changes to future performance, this does not seem logical.

If history is any guide, then we should see relatively volatile performance over the next five years, as current Switch volumes decline but are then replaced by something new, which may or may not be successful. The timing of a new console launch could have an important impact on the extent of this volatility. My rough expectations are for it to drop mid calendar year 2024, but if it comes sooner, then there is less downside to volume and revenue in the next two years. In either scenario though, EBIT and Net Income should receive some benefit from expanding gross margin as a result of the rising share of digital sales in software revenue.

If you subscribe to the view that Nintendo is pivoting its model toward more of an ecosystem, in which future hardware and software releases become more frequent and iterative, then you would surely expect less revenue cyclicality and a steady upward slope in revenue, profits and cash flow over the coming years. Yet this is not what the consensus numbers below show, suggesting this is also not the scenario being projected.

A prima facie conclusion from this comparison suggests that a new console being released at some point in the next five years would be a positive catalyst for the stock, since consensus numbers are not factoring this in. But I am not so convinced that these consensus numbers really reflect what the market thinks. I struggle to imagine that any attendant observer of Nintendo does not expect a new console of some kind in the next two years, including sell-side analysts. People might differ in how successful they think that console will be, but I struggle to imagine anybody does not expect one. Having been on the sell-side myself, I have seen that sell-side analysts on occasion feel more comfortable extrapolating what is known rather than making audacious calls about what is not yet known. Therefore, one could conjecture could be that this picture reflects more the shortcomings of the sell-side forecasting process than genuine market expectations. But that could be wrong and, if it is, then a new console being released should indeed move the stock, assuming it is well-received. A new console that does very well should move the stock regardless, at least in the short-term.

Valuation

In assessing the attractiveness of Nintendo’s valuation, my approach is to consider relative valuation versus a selected group of listed gaming and media companies (see table below). I pulled peer group multiples from atom.finance for the next three years. Unfortunately I was not able to get these for the next five years. As a brief aside, I did not think a DCF approach would be very useful here, as I am forecasting relatively volatile cash flows for Nintendo over the next five years with some degree of uncertainty. This means that the base year (year 5) for a terminal value projection could end up being non-trivially over or under inflated, yielding an over or under inflated intrinsic value. So it seems more useful here to look at relative valuation.

Across EV/Revenue, EV/EBITDA and P/E multiples, Nintendo is trading at a discount to the peer group median in FY1 but this discount narrows toward FY3. Looking at FCF yield, Nintendo offers a superior yield in FY1 and FY2, but dips below the median in FY3. As for dividends, Nintendo’s yield of ~3% over the next three years, while not amazing on an absolute basis, is a lot more attractive than the peer group.

Overall, the relative valuation does not scream out as cheap, but it does look undemanding. It is worth remembering that this valuation is reflecting the end of a console cycle, in which I am forecasting rapidly declining Switch hardware and software volumes. The impact of a new console does not show in my estimates until FY4 (hence a shame I couldn’t get peer group multiples looking 5 years out). In that context, the fact the valuation looks at all decent is quite positive. If I turn out to be wrong in expecting a quick descent for the Switch and/or the new console drops sooner than I expect, then Nintendo would likely look more attractive.

That said, we should consider Nintendo’s relative valuation alongside the short and long term investment case for the stock.

On a short to medium term view, there is a strong potential positive catalyst in the form of gross margin expansion on the back of increasing digital sales of game software. I also suspect that a new console dropping some time in the next couple of years could act as a positive short-term catalyst, assuming it is well-received. If you take these potential catalysts alongside a relative valuation that is undemanding even when reflecting the downward slope of a console cycle, then risk/reward seems favourable.

Looking to the long-term, however, there is a large degree of uncertainty. Whether the economic moat around the business widens or narrows in the future depends on what decisions management takes regarding the level of investment in IP and on whether they loosen their quasi-religious attachment to who and what Nintendo is and does today. Will the company invest more in mobile gaming? Will they change their approach to offline IP initiatives? The other crucial question is how successfully the company reduces revenue cyclicality, as persistent cyclicality will warrant a persistent discount in the valuation. On both these questions, management’s commentary strikes the right notes and they are pursuing the right strategy on paper. However, management’s actions (as indicated by the level of investment) convey that a strong element of conservatism remains.

Excellent read. Thanks for posting.